More than 680 gray whales have washed up or been found dead on North America’s Pacific shores over the last four years, a rapid die-off that has puzzled and frightened scientists.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, which publishes data on whales found dead, classified the spike in gray whale strandings as an “unusual mortality event.”

So researchers began to probe the mystery: Were the massive mammals being hit by ships, tangled in fishing gear or stricken with disease?

A new study, published Thursday in the journal Science, offers an answer: Changes to sea ice conditions in the Arctic appear to be causing gray whale populations to boom and bust based on shifting access to the tiny shrimplike creatures they eat.

“We’ve kind of cracked the case of these big die-offs, and we’ve found they happen more frequently than we expected,” said Josh Stewart, an assistant professor at Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute and a lead author of the paper.

Stewart’s team found that the whales’ population appears linked to the length of time that sea ice blocks their access to feeding grounds in the Arctic and to the quality of food available when the whales are there.

It comes down to “how much food do they have and how long do they have to eat,” Stewart said.

Climate change has played a role recently — the extent of Arctic sea ice varies widely year to year, but rising temperatures are causing a long-term decline. Initially, that decline opened more days of access to feeding grounds for gray whales. But Arctic warming has also set off a slew of other changes — to currents, water temperature and sea ice algae — that have reduced the quality of the whales’ food.

“They’re not making as good a living,” Stewart said.

The new study offers evidence that sea ice variability was also behind two prior gray whale mass death events, including a well-documented die-off that began in the late 1990s. The findings suggest, as well, that climate change could limit the number of gray whales that can survive in the future, as diminishing sea ice impacts the population of tiny, seafloor-dwelling crustaceans the whales love to eat.

Most North Pacific gray whales migrate more than 5,000 miles twice a year, spending their winters in warm lagoons off Mexico, where they can safely raise calves and reproduce, then feasting in the Arctic during the summer.

In those Arctic feeding grounds, gray whales dive to the bottom of shallow basins, suck up sediment filled with crustaceans called amphipods, and then filter out the food from the mud.

The enormous creatures — which can reach nearly 50 feet in length, weigh about 90,000 pounds and have been documented living as long as 80 years — spend only about four months feeding, Stewart said. The rest of the year, they mostly fast.

“They really have to gorge themselves for those four months,” Stewart said.

For the new study, Stewart’s team analyzed data from long-term monitoring programs to evaluate whales’ abundance, reproduction, deaths and body condition over the past 50 years. From those numbers, it was clear that gray whale populations have had periodic booms and busts. The scientists then compared that data to the animals’ level of access to their feeding grounds and the abundance of crustaceans, finding a pattern.

Researchers have long suspected that Arctic conditions could be impacting gray whales, and past studies have investigated whether the availability of prey could play a role in die-offs.

The new findings show convincingly that there’s a relationship between ice cover and variability in gray whale populations, said Elliott Hazen, a research ecologist at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, who was not involved in the new study.

“We have a clearer idea of what happened,” Hazen said.

Once ravaged by 19th and 20th-century commercial whaling, North Pacific gray whales became a beacon of conservation success after the 1960s, as federal protections and international whaling restrictions led their population to boom. The species is protected by the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act and the International Whaling Commission.

Since the height of the whaling industry, when gray whale blubber was used for oil, the animals have made a remarkable recovery.

“Gray whales have been one of our quickest rebounding populations,” Hazan said.

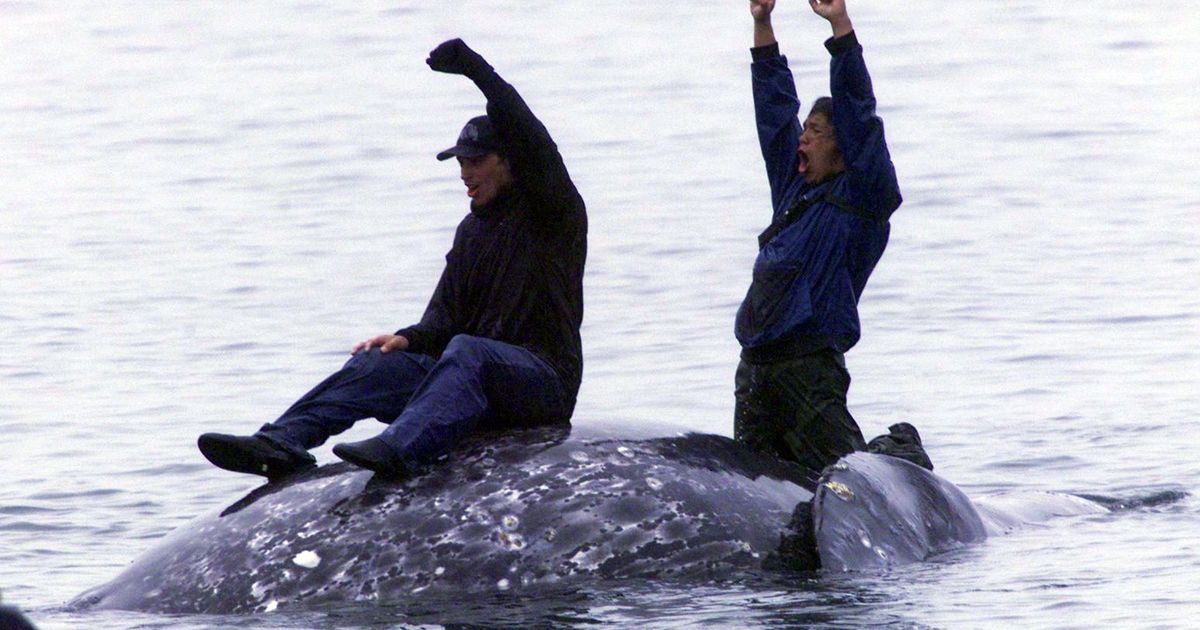

But in 1999, hundreds of whales began washing up dead on beaches in the U.S., Mexico and Canada. Scientists knew many more were dying away from human view.

“For every whale that washes up dead, there are 20 that die that don’t wash up,” Stewart said.

When the same pattern played out again two decades later, scientists began to dive deeper. The new study puts the recent rash of deaths into context and highlights the threats the species faces going forward.

The North Pacific gray whale population had surged to about 27,000 by 2016, according to NOAA estimates; today, the number is closer to 14,500.

Stewart said he’s not worried that gray whales will go extinct. The mammals have persisted through ice ages, periods of warming and tens of thousands of years of changes to their prey — not to mention a period of extensive human hunting.

“They’ve lived through major climatic change in the past. They’re quite adaptable,” Stewart said.

But Arctic warning is now a major problem for the whales, one that Stewart said could ultimately limit the number of mammals sustained by the feeding grounds.

“That’s a tough thing to swallow,” Stewart said. “We’ve locked in changes that may have altered how many whales they can fundamentally support.”